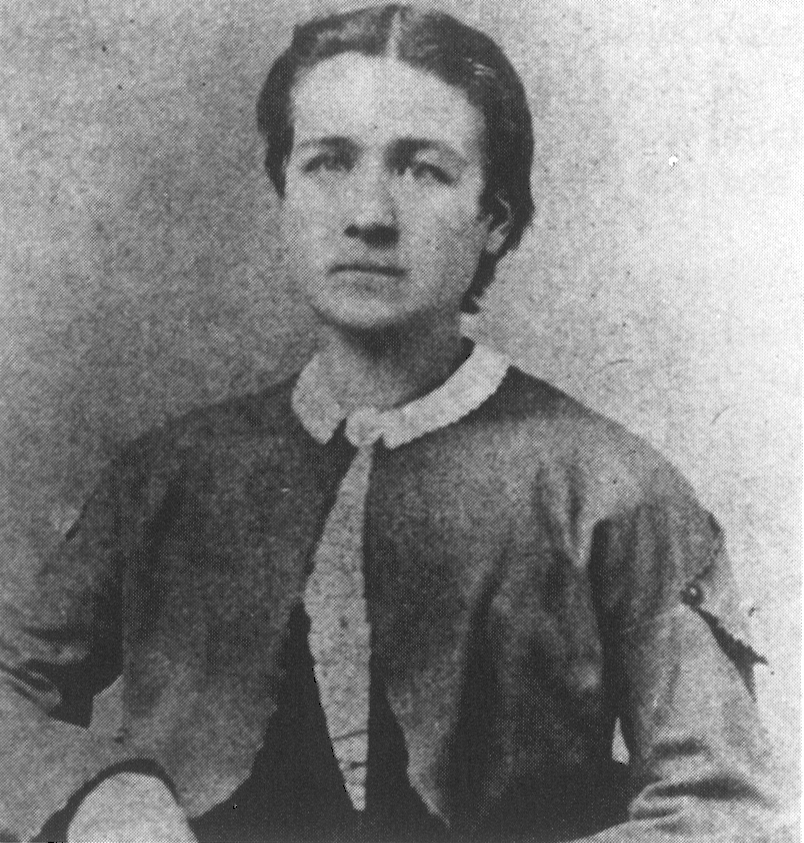

Lucy Hobbs opened the door to dental school for women 150 years ago

As you know, the ODA has been celebrating its sesquicentennial anniversary throughout 2016. The ODA’s founding, however, was not the only significant dental-related event that happened in Ohio in 1866. That same year, Lucy Hobbs became the first American woman to earn a dental degree when she graduated from the Ohio College of Dental Surgery.

Hobbs’ unconventional life began in upstate New York where she was born in 1833. Her mother died when she was around 9 years old. Shortly after her mother’s death, her father married his sister-in-law, who then died just two years later as well. Throughout her life, Lucy believed that this experience of losing her mother and step-mother led to her strong independence. Lucy attended boarding school in New York between 1845 and 1849, receiving an education sufficient enough to allow her to begin a teaching career at age 16.

She moved to Michigan where she taught school for 10 years. While in Michigan, she developed an interest in medicine. At age 26, Hobbs moved to Cincinnati with the intent to study medicine at the Eclectic Medical College. She was denied admission because of her gender and was advised to consider a career in dentistry instead of medicine.

At the time, dental education usually began with a preceptorship with a dentist, followed in a minority of cases with enrollment in dental school on the recommendation of the preceptor. In 1861, there were only three dental schools in the United States: The Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, founded in 1840, the Ohio College of Dental Surgery, founded in 1845 in Cincinnati, and the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery, founded in Philadelphia in 1856. Many dentists entered practice only having completed a preceptorship, while others spent a term or less in a dental college without earning a degree. At the time, a significant minority of practicing dentists actually earned a dental degree.

Hobbs had difficulty finding a preceptorship as most male dentists felt it could be damaging to their careers if they were to take in a female student. She began studying under Jonathan Taft, who would later serve as president of the ODA and ADA and also served as dean of the Ohio College of Dental Surgery. After three months studying with Taft, she finally landed a preceptorship with Dr. Samuel Wardle, who was a graduate of the Ohio College of Dental Surgery.

Hobbs said of Wardle: “To him alone belongs the honor of making it possible for women to enter the profession. He was to us what Queen Isabella was to Columbus; may his name, like hers, be revered by every woman in the profession.” While she was studying with Wardle, she paid her expenses by sewing clothes for others after hours. After several months studying and training with Wardle, Hobbs applied to the Ohio College of Dental Surgery but was denied admission because she was female.

Despite her rejection from the Ohio College of Dental Surgery, Hobbs was not deterred. Wardle encouraged her to open her own dental office, even though she did not have a dental degree. She opened her practice in Cincinnati in 1861. Her timing could not have been worse as the Civil War broke out just as she was opening her new dental practice. The following year, she moved to Iowa to get further away from the war zone. She opened a dental practice there and quickly established a strong reputation as “the woman who pulls teeth.”

Her practice in Iowa was successful, and in 1865, the Iowa State Dental Society changed its bylaws to allow women into membership. On July 19, 1865, Hobbs was elected into membership of the Iowa State Dental Society, becoming the first woman in history to become a member of a state dental society. At that same meeting of the Iowa State Dental Society, Hobbs was named as a delegate to the American Dental Convention, which met in Chicago later that same year. In Chicago, the Iowa State Dental Society’s delegation made a strong push for the Ohio College of Dental Surgery to admit Hobbs into its program. It worked. The Ohio College of Dental Surgery accepted Hobbs, and she moved back to Cincinnati to enroll in November 1865.

Because of her years of study and practice, she was required to attend less than one year of classes. In 1866, she received her diploma from the Ohio College of Dental Surgery along with the 15 men in her graduating class, making her the first woman to receive a dental degree.

Hobbs impressed her teachers. Upon graduation, Dr. George Watt, who was the first president of the ODA and taught chemistry at the Ohio College of Dental Surgery, said of Hobbs: “She is a credit to the profession of her choice and an honor to her alma mater. A better combination of modesty, perseverance and pluck is seldom, if ever, seen.”

Taft said that Hobbs “was studious in her habits” and “had the respect and kind regard of every member of the class and faculty.”

Following graduation, Hobbs moved to Chicago where she practiced for a little more than a year. She then relocated with her husband to Lawrence, Kansas, where she had a successful dental practice for more than 40 years.

While dentistry remained a male-dominated profession for many decades following Hobbs’ graduation, there has been a significant change in recent years. According to data collected by the ADA’s Health Policy Institute, only about 1 percent of dental students were female in 1968. By 1978, that number had risen to about 15 percent, and today, almost half of all dental students in America are female. In fact, in 2016, a majority of the graduating class from the Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine was female for the first time in the school’s history.

Lucy Hobbs’ trailblazing persistence 150 years ago opened the door to dental education for the thousands of women who followed in her footsteps.